Panning for Fools’ Gold

Why chasing America’s sports model is a mirage - and why UK and European games thrive when they trust their roots.

"Our games should remember that influence is not a one-way tide...the rivalries weathered over generations, the stories handed down, the folklore no amount of money can mint. These are treasures the Americans themselves might quietly covet, for the depth and identity we too often take for granted. "

Matt Hennessey

The late-summer warmth hung over Philadelphia, each breath carrying a trace of the season. Out on the field, English rugby union’s Saracens and Newcastle Falcons were playing a league fixture in a stadium built for an entirely different code, before a crowd that didn’t seem entirely sure when or why to roar.

In amongst the sparse and bemused locals, a pocket of English expatriates bellowed in the corner, their voices thinning against the emptier banks of seating that dominated the ground. The smell of hot dogs drifted across the turf. Beer cups sweated in the pale sun. The spectacle felt both familiar and counterfeit - like a retired High Court judge arriving at Twickenham’s West Car Park in a sequined Elvis jumpsuit.

In recent years, UK and European sport have been peering westward with an almost romantic longing - two great rivers running close enough to hear each other but never meet. They pass like Atlantic liners in the shipping lanes: the NFL sending its crown jewels to Germany, the NBA sprinkling stardust on Paris, and MLB pitching up in London to plant a flag. Our return voyages feel meeker - not ocean giants, but modest convoys: Warrington and Wigan bound for the Nevada desert, or two rugby union teams on the banks of the Delaware River who, within living memory, played on public parks. Even the Premier League - a commercial juggernaut - offers only the polite courtesy of pre-season friendlies, guarding its competitive heart like a family heirloom too precious for foreign waters. And still we chase the mirage of “cracking America,” as if the most saturated sports market on earth were waiting, arms open, for our deckchairs and flasks.

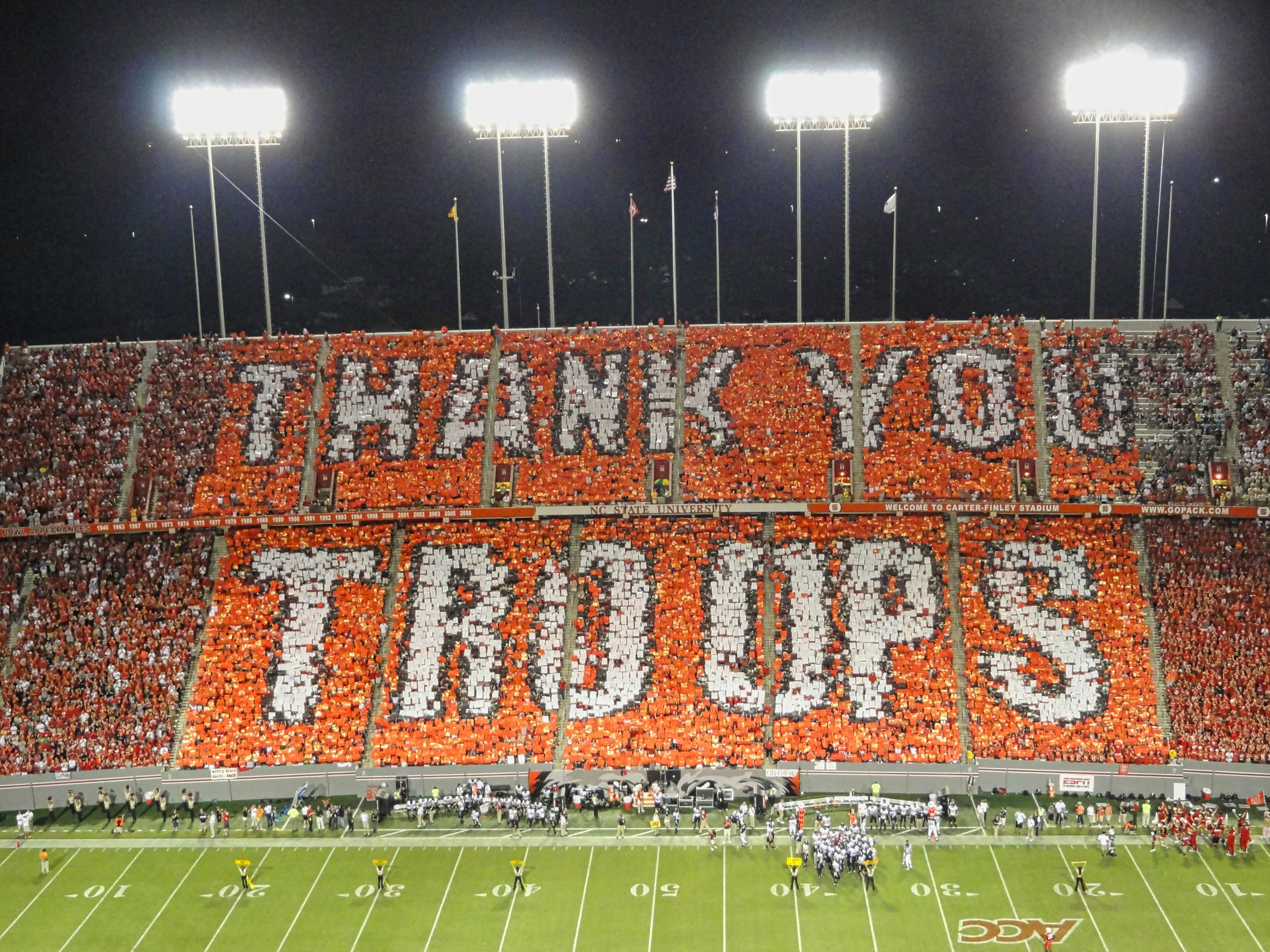

Here’s the thing: our sporting culture is not America’s, and no amount of marketing bravado will make it so. That’s not small-mindedness; it’s an acceptance of difference. The American model is a creature of its exceptionalism, and its own soil - of tailgates in vast car parks, of marching bands spelling out logos big enough to be seen from the cheap seats, of national calendars built around television events as if they were harvest festivals.

Photo by Gene Gallin on Unsplash

Photo by Gene Gallin on Unsplash

The Cultural Chasm: Why America’s Sports Model is Alien to us.

Writer Evelyn Waugh once skewered - with his typical snobbish misanthropy - the American gift for hearty overfamiliarity - the stranger calling you “buddy” before you’ve even spoken, the ritual carried out with relentless cheer. That instinct, genuine or not, runs deep in its sport: part show, part sermon, brimming with confidence in its own form. You see it in end zones flanked by giant video screens, or Jumbotrons, that replay a touchdown from every angle before the extra point, in halftime fireworks choreographed to the TV break. It thrives in an ecosystem that feels foreign to the UK and Europe.

In America, the leagues are closed citadels. No promotion, no relegation - only franchise rights guarded like deeds to the family ranch. One vast market is enough to feed the NFL, NBA, MLB, and NHL without them ever needing to look abroad, save for the luxury of doing so. The collegiate system is its own industrial miracle, producing athletes, filling campus stadiums, captivating television audiences, and lifelong loyalties before a professional contract is even signed. The television calendar is full to the brim; the Super Bowl and March Madness are not just competitions but national holidays.

Europe is a map of open leagues, curious cup competitions, and porous hierarchies. Clubs rise and fall. They are stitched into industry, sectarian lines, clans, political movements, neighbourhoods and towns. They are febrile, fervent and familiar. Not vehicles for branding plans.

The market is gloriously fractured across nations, languages, and governing bodies. Football in England is not football in Poland; rugby in Barrow is not rugby in Biarritz. Each plays to its own rules, accents, and affections - a patchwork that resists being sewn into a single cloth.

If American sport is Ancient Rome - centralised, ordered, every road leading to a single empire – European sport is a scatter of Greek city-states, each suspicious of one another and equally proud of its own ways. Rome’s triumphs don’t translate wholesale into the agora.

The chasm isn’t about rules on paper; it’s about how a culture conceives of sport itself. In Europe, defeat can be heroic, community expression can be victory enough, and survival in the league can matter as much as silverware. The American model has little room for such antiquated heresies.

Take Wrexham’s Hollywood revival in football. It has thrived not because its A-list owners arrived to carve their initials in the club’s history, but because - remarkably for men used to command performances - they understood that the story worth telling was already there. Their role was to amplify the civic pride and sense of place, not overwrite it. By contrast, Tom Brady’s uneasy turn in Birmingham City’s recent documentary had the air of a parachute drop - an entrance timed for spectacle rather than acquaintance. It brushed the surface but never touched the understanding that quietly keeps a club alive, the pulse you only find by standing still long enough to hear it.

The Commercial Mirage: Why the Numbers Don’t Add Up

The Financial Times likes to say that comparing Britain’s economy to America’s is like comparing a market town to Manhattan - the scale is different, the mechanics alien. On one side, a Saturday stallholder in drizzle; on the other, a skyline that glitters even in the rain.

Sport follows the same law, especially in the niche codes. America’s population, GDP, and single, borderless media market feed each other in a closed loop of sponsorship, ticketing, and broadcast revenue. One domestic TV deal there can underwrite the wage bill that, in Europe, takes a year of juggling debts, favours, and investor patience.

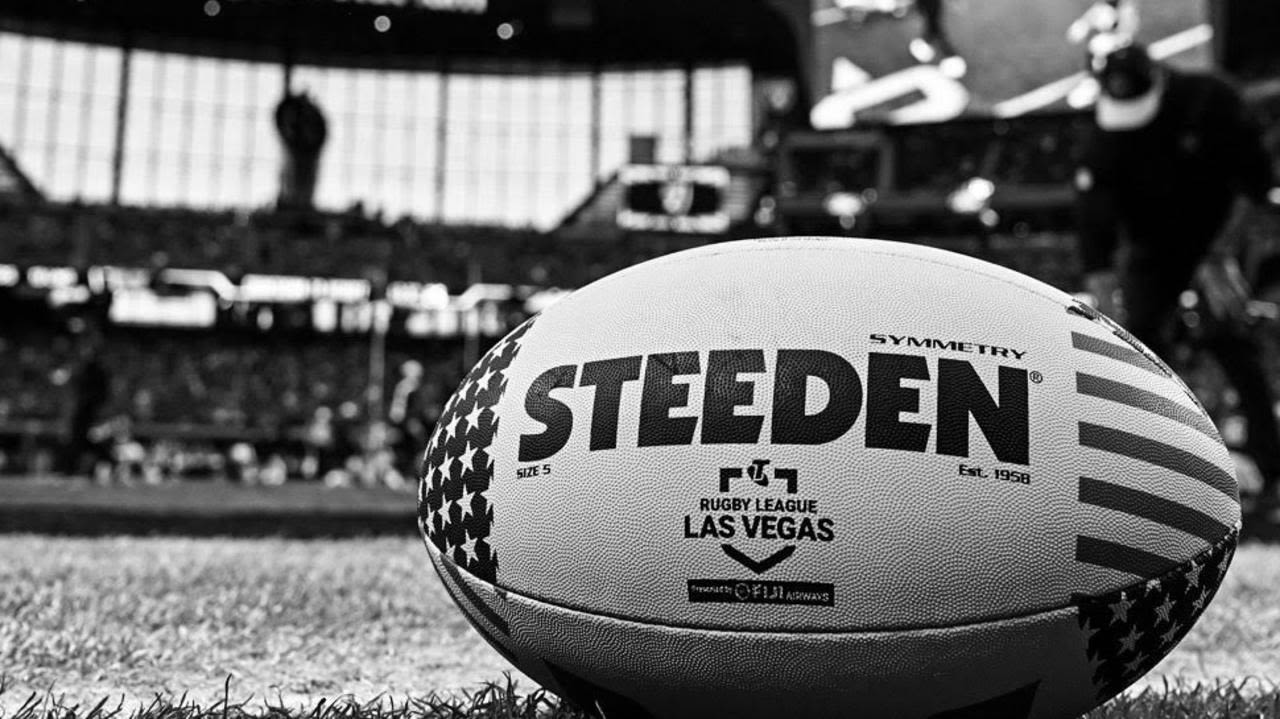

But when our leagues look west, they often mistake the size of the prize for its reach. Rugby League’s much-trumpeted Las Vegas gamble promised visibility and new fans. In reality, most of those who made the trip could have had their passport stamps traced straight back to the M62 corridor - loyal pilgrims rather than wide-eyed converts. Premiership Rugby’s forays - Saracens in the States against London Irish and Newcastle Falcons - flirted with the same pattern. The spectacle makes the trip; the substance stays at home.

I remember Saracens’ trips to New Jersey and later, Philadelphia, vividly. The logistics alone were punishing: players blinking into new time zones, training on pitches that felt like borrowed land, and a skeleton staff trying to sell rugby in markets where it was a polite curiosity at best.

Saracens players training on a University campus in Philadelphia in Sept. 2017 ahead of Premiership Rugby league fixture againts Newcastle Falcons

Saracens players training on a University campus in Philadelphia in Sept. 2017 ahead of Premiership Rugby league fixture againts Newcastle Falcons

Some moments played well for the cameras - a few corporate boxes filled, expats grinning in familiar colours, a ceremonial first pitch tossed to dutiful applause, local news crews getting their soundbite. But the numbers told a plainer tale: interest without investment, awareness without allegiance. It was like turning up to a gunfight armed with a soup spoon - earnest effort, but never in the right league.

Even La Liga, glossier and more recognisable than most to a US audience, is now chasing its own Gold Rush - a competitive league fixture in Miami that feels less like expansion than theatre: a bold gesture bound to be tangled in legal disputes, soured by fan backlash, and shadowed by the unspoken question - who, exactly, is this for? The allure is spectacle, but the aftertaste could be that of Steinbeck’s dust-blown caravans: chasing the promise of orange groves in Florida when the trees in Seville are already heavy with fruit.

The ‘Special Relationship’ – The Mirage of Mutual Interest

For all their occasional forays overseas, America’s biggest leagues are not losing sleep over European competition. Why would they? Their home market is vast enough to feed the NFL, NBA, MLB, and NHL for generations, with audiences in the tens of millions and TV deals locked in years ahead. The NCAA alone stages more major events in a single season than most European rugby nations could produce in a decade - from bowl games to March Madness - each drawing crowds and coverage that dwarf our domestic finals.

Yes, they come to Europe - the NFL fills Wembley and Munich, the NBA packs out Paris - but these are big-league branding exercises, deployed from a position of strength. They are not existential lifelines; they are victory laps.

Now hold that scale in your mind and compare it to our own “expansion” plays: a couple of rugby league clubs decamped to Las Vegas for a weekend, or a pair of Premiership sides shunted onto a US sporting backwater. No television saturation, no vast marketing machine, no legacy footprint - just the novelty value of seeing a sport most locals couldn’t name in a quiz. It is hard to see these ventures as anything but egotistical gestures, thrown out into a market that didn’t ask for them and will forget them by Monday.

Europe’s media landscape is fractured by borders, languages, and competing codes; there is no single market to sell into. The Premier League and Champions League can still thrive despite that, but for smaller sports, “breaking America” isn’t just a long shot - it’s walking into a casino with pocket change and thinking you’ll buy the place.

And here’s the danger: every hour spent chasing that mirage is one not spent watering our own fields. We risk teaching our fans that the applause over there counts for more than the loyalty here. It’s not mutual courtship. It’s a guest list we don’t control, at a party we weren’t invited to. And if we keep chasing those invitations, we might find our own stands emptier when we get home.

Watering the Grass Beneath Our Boots

I keep coming back to a line I’ve written before: ‘We must stop chasing concepts and water the grass beneath our boots’. That isn’t nostalgia. It’s vital. The glitter of the Super Bowl halftime show or the NBA’s marketing muscle can dazzle, but they are no measure of the worth of our games.

Where the Shadows Fell Long takes you to the coal towns where rugby of either code was a ritual, and asks what we lose when sport forgets its roots

Far from being impoverished by its difference, sport in the UK and Europe carries a wealth the glossy exports can’t counterfeit. It will thrive when it trusts its own rituals and rivalries, instead of glancing across the Atlantic for a template we never needed. Its value lives in the stubborn loyalty of a fan who stands in the rain for a relegation scrap in Castres, Castleford, or Catania. In a club crest that can map a century of civic history in Livorno, Leeds, or La Coruña. Here, clubs are rooted in place. There, teams like the Raiders drift from Oakland to Los Angeles to Las Vegas, or the Colts from Baltimore to Indianapolis - rootlessness ruthlessly accepted, curiously celebrated.

Lower league Italian football, where generations of one family watch their local team, Sorrento Calcio

Lower league Italian football, where generations of one family watch their local team, Sorrento Calcio

To build on our strength is not to lower our sights; it is to set them on ground that will hold. If the grass is greenest where it’s watered, then the task is plain: tend to our own fields, as the fans of Salford RL, Worcester RU, and Bury FC already know. Honour the structures that have held us together, because once those roots are gone, no amount of borrowed glamour will bring them back. Adapt, yes, but not at the cost of erasing what makes our games ours.

The American political scientist Robert Putnam, in his work Bowling Alone, used the decline of ten-pin bowling leagues from the 1960s onward to warn of fraying community bonds. His point was not about pins and balls but about the quiet collapse of shared rituals - the Friday night lights, the Little League diamonds - that once stitched towns together.

We have not yet walked that road, though the roll call of losses is already long enough to shame us. Across much of the UK and Europe, clubs remain anchored to place, from the floodlit tiers to the windblown village pitch. Global branding can serve that bond - as Liverpool and Nike proved with their “Scouse, not English” salute - but when the tether to locality snaps, all that’s left is a logo adrift. Our advantage lies in that rootedness. To surrender it in pursuit of markets that neither need nor particularly want us would be to trade something lasting for something passing.

History tells us that for smaller sports, the great American breakthrough rarely arrives. Rugby league’s Vegas weekend, Premiership Rugby’s U.S. detours - each brought a spike of novelty, a few curious headlines wrapped and little else. Even the NFL and NBA, with their colossal machinery, treat foreign trips as branding exercises, not lifelines. If they can afford to treat it lightly, why should we mortgage our substance for the same stage? We have a sporting culture rich and resilient enough to thrive on its own terms.

It used to be said that when the U.S. sneezed, the world caught a cold; as former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers observed, the reverse can be just as true. Our games should remember that influence is not a one-way tide. We are richer when we tend the roots that give them their life - the rivalries weathered over generations, the stories handed down, the folklore no amount of money can mint. These are treasures the Americans themselves might quietly covet, for the depth and identity we too often take for granted. Bill Bryson once lamented that Britain had “a near-total disregard for anything old,” a kind of cultural vandalism dressed up as progress; in sport, the same mistake would be to swap gold for gilt, and call it an upgrade.

I’ve seen what that trade looks like. I remember the futility of that day in Philadelphia - the knot of expats bellowing into half-empty stands, their voices fraying into the space between them. They meant every note, but the sound never found an echo. Let those voices rise where they can take root - in Castleford’s drizzle, in Livorno’s sun - where the roar carries, where it belongs, and where, crucially, it will be met in kind.