The Last Voice in the Living Room

Remembering Ray French

"Ray French didn’t just commentate on rugby league. He dignified it. Not with pomp or pretence, but with a tone that matched the game’s virtues: honest, hard, unvarnished, and deeply human."

Matt Hennessey

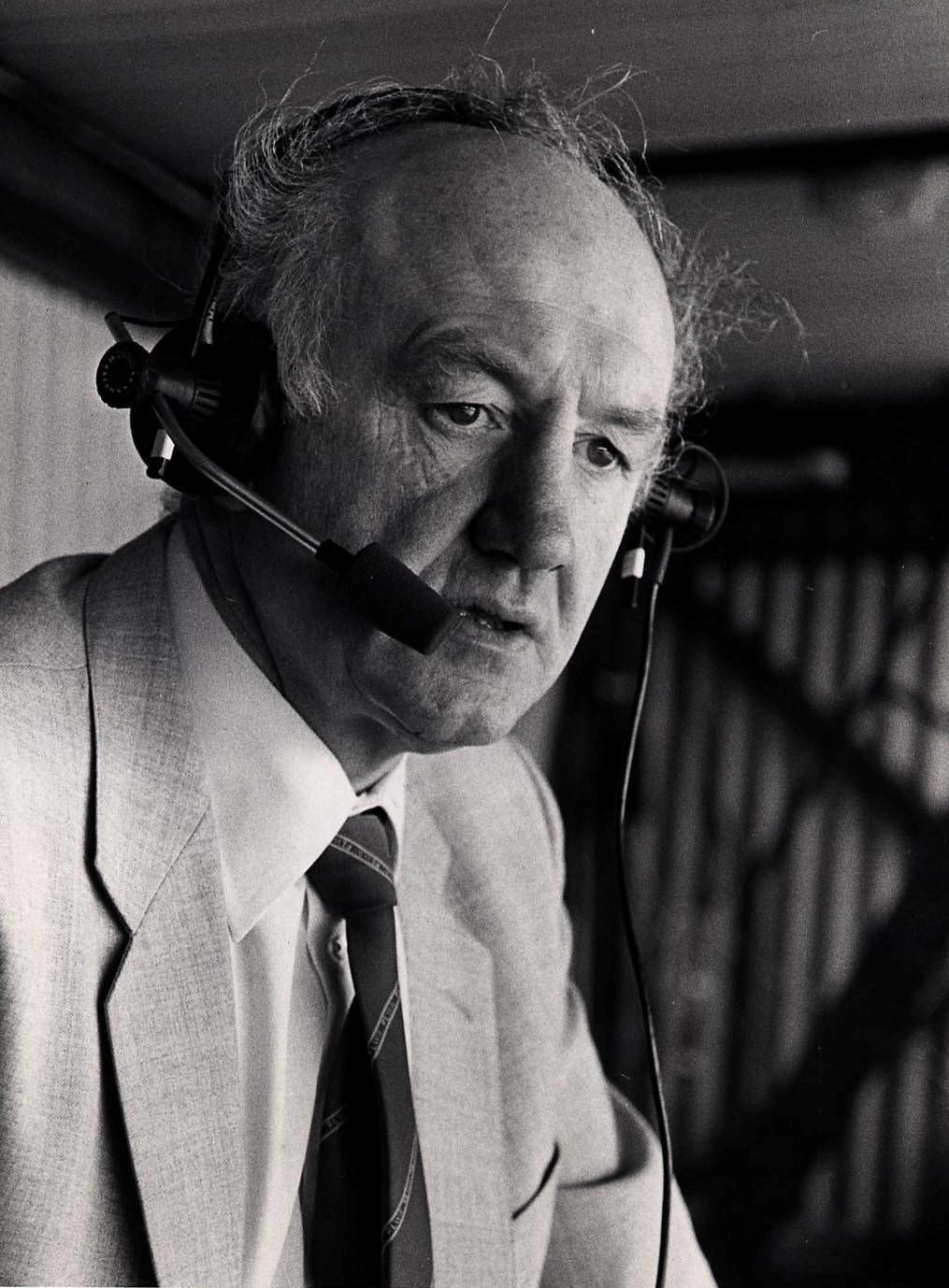

Ray French, who this weekend sadly passed away aged 85, did not merely commentate on rugby league. He cradled it in his voice.

In an age before branding overtook belonging, his tones carried the game from the pithead to the parlour, from Wembley to the working men’s club, with a warmth that never once mistook sentiment for indulgence. He didn’t sell the spectacle. He understood the soul. For decades, he came into our homes not as an intruder but as inheritance - the steady voice on the telly that made Saturday feel like Saturday, and the game feel like it still belonged to those who needed it most.

There was a time - and it is not so distant that we cannot still feel the warmth of its glow -when rugby league carried a place in the national consciousness that was not begged for, but quietly assured. Before it was consigned to obscurity from Fleet Street or regional tokenism via a red button, it stood tall in the national schedule. Wembley was full. The BBC cameras were rolling. The voice was Ray French.

Let’s cast our minds back. Wembley, 1994. Great Britain against Australia. A contest taut with history and dread, and then, from the shadows of his own half, dual code star Jonathan Davies cuts through the Kangaroo line like a man conducting his own jailbreak. There’s a twitch of the hips, a sleight of foot, and suddenly the old ground seems to tilt downhill in the Welsh wizard's favour.

And from the commentary box, Ray French - never hurried, never ostentatious - lets out a line that is half delight, half disbelief: “Davies… he’s got some space!” Not shouted. Not dragged from a media handbook. Said with the enthusiasm of spotting an old friend in a crowded room.

“He’s going for the corner! He’s got his head back…And the Welshman is in for a magnificent try in the corner!”

You didn’t just watch it. You felt confirmed in it. The try was brilliant. But it mattered because French said it did. Said with passion and precision.

It was one of those broadcast moments that doesn't just describe history. They help shape it in your consciousness. The scoreboard in BBC Grandstand yellow italics. The sunshine on the old turf. The crowd surging in those great Wembley arcs. The Green and Gold and Red, Blue and White chevrons. And French’s voice - unmistakably of its place, wonderfully rooted - giving the moment its moral register. That try might have frightened the Australians. It might have stunned the neutrals. But it made sense to us because French said it did.

To understand what we’ve lost in Ray French, perhaps it helps to think less of what he said and more of when, where, and how we heard him.

He belonged to that small, vanishing cadre of men - Bill McLaren in union, John Motson in football - whose commentary was not merely descriptive, but domestic. They didn’t arrive through curated content or niche subscriptions. They came through the aerial, through the carpeted warmth of the family home, through the flickering certainty of a 3:15 kick-off and a mum making a brew in the kitchen. They were not summoned. They were simply on.

Sport, back then, was not demand-driven. It was calendar-bound, a weekly sacrament. You did not seek out a match. It came to you through a fixed channel, at a fixed time, on a fixed day. And with it came the voice. McLaren, with his Border bardism. Motson, with his sheepskin precision. French, with his Lancastrian lyricism. You didn’t select them. You grew with them. And in that growth, a strange intimacy was formed. Not personal. But deeply familiar. They entered the home like old uncles, never flashy, never late, never trying too hard to entertain.

Now, we stream. We clip. We choose. Sport, like everything else, bends to convenience. But in doing so, something softer fractures. The shared experience becomes individual. The communal clock, that beautiful ticking certainty of the Saturday schedule, falls silent. The voices we used to know give way to rotating panels, guest experts, ex-pros with polished diction and all the depth of a podcast thumbnail.

Ray French did not belong in a thumbnail.

He was part of the mantelpiece. Part of the trusted clutter of British sport. Not performative. Not replaceable. Just reliably, comfortingly there. And in that stillness, that steady place he held, he was ready - when it truly mattered - to turn a fleeting act into something unforgettable. Like he did with Jiffy’s try. Like he did with Ellery Hanley’s breakthrough score for Bradford Northern, and like he did for Brett Kenney's and Martin Offiah’s Wembley wonders. He had a gift, not just for the game, but for the punctuation of it. Those tries were all a sentence. French gave them their full stop. And in doing so, gave them all permanence.

There’s a detail worth holding onto. Years later, after Davies had swapped the boots for the microphone, he found himself alongside French in the commentary booth. The scorer beside the narrator. The spark beside the steward. Together, they called new matches - but you always felt like they were revisiting that one. The try had given French a line. But French had given it memory.

The try that Davies ran, French ran with him. And when Davies later picked up the mic, he was still chasing the echoes.

We all were.

Ray French didn’t just commentate on rugby league. He dignified it. Not with pomp or pretence, but with a tone that matched the game’s virtues: honest, hard, unvarnished, and deeply human. French never sold the sport as something it wasn’t. He simply told you why it mattered - by treating it like it already did.

And he did so not out of obligation, but from reverence. He knew what it meant to those who played it and those who lined the terraces in threadbare coats. He spoke for them, not at them. He wasn’t just an employee of the BBC. He was an envoy of a game that had given him everything — and he spent the rest of his life paying it back, one phrase at a time.

And maybe that’s the mark of a true custodian: not that they made the sport about them, but that they made it more itself.

RIP Raymond James French MBE.